Some things in animation don’t change. During the jump from pencil-and-paper animation techniques to digital art and animation, the core basic animation principles remained the same. Many of these key animation principles are laid out in the book “The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation,” written by Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas — two of the legendary Disney animators that make up “Disney’s Nine Old Men.” While techniques and tools have expanded far beyond pen and paper, it’s worth re-examining how some of the basic animation principles celebrated by Johnston and Thomas still apply.

Animation Principle #1: Squash and Stretch

Considered the most important animation principle in “The Illusion of Life”, squash and stretch is essential for showing motion in animated works. Consider a bouncing ball — instead of drawing a perfect circle for each part of the bounce, you’d draw it flattened at the low part of the bounce, and then stretched as it leaves the ground. This animation principle shows the energy behind its motion. It’s also applicable to a character walking, talking, acting, well everything! — particularly when it comes to exaggerated facial expressions and motion. 3-D animation work has to balance this with the rigging that provides shape to an animated object — and it will entail more complex rigs to allow for the sometimes cartoonish level of distortion needed. Some projects and digital art work will require more realism than others, but even these projects can benefit from squash and stretch to convey kinetic motion. For example, the Disney film Tangled uses exaggerated squash and stretch in its light-hearted scenes to convey comedic action.

Animation Principle #2: Anticipation

Motion doesn’t just happen, of course — there’s build-up to it, and that build-up is another key animation principle called anticipation. Somebody jumping has to crouch down first, and a baseball pitcher has to wind up before pitching. In this animation example from the film Tres Caballeros, the character crouches down slightly before he jumps. That leading animation not only prepares an audience for the main action, but lends realism to animation work that requires it. Longer anticipations can help give weight to a bigger action.

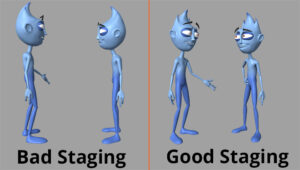

Animation Principle #3: Staging

You only have so much time in an animation, so every scene and frame needs to work toward telling the overall story of a project. You can’t clutter your work with too many actions at once, unless your goal is to show chaos and confusion. The animation principle says the pose of a character or an action should be showing your audience a character’s attitude and reaction as it drives the plot forward — as well as show as much of the character as possible. The pose and positioning of the main character of Paperman in the opening scene not only convey a bored attitude through his slouched shoulders, but show that he’ll soon be joined in the frame by putting him off to the left.

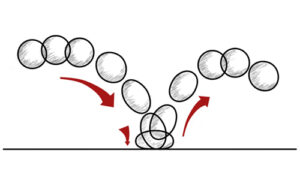

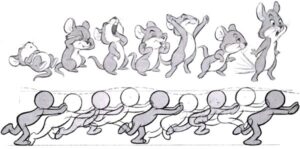

Animation Principle #4: Pose to Pose and Straight Ahead Action

These two animation principles are techniques that provide different kinds of energy to an animation. One of the animation principles is called pose to pose. As seen at the top of the picture, pose to pose has several key, fully fleshed-out frames of animation drawn at the start of work on a scene. The animator takes his or her time on these key frames and poses, and then another animator — or a computer program — fills out each frame between the key poses. By using the pose to pose method, an animator can better control the size, volume and proportions of an animation — which is great for emotional and dramatic scenes.

The other animation principle is straight ahead animation. As seen at the bottom of this picture, straight ahead action quickly works from the start to end of a scene — each frame is drawn out in sequence, often blending frames together. It brings spontaneous energy to a scene at the cost of some size, volume or proportions of the model. According to Siggraph, straight ahead animation is good for fast action scenes.

Most animation examples borrow from a bit of both of the pose to pose and straight ahead animation techniques. You can see examples of both in the trailer for the Project X production Worlds Apart — for example, the scene where the boy points shows a transition between a few key poses.

These are four of the 12 key principles of animation, an important place for those new to digital animation to begin. If you’re just getting started in your digital art and animation career, you can also learn more about essential animation design software, or check out more of our Digital Art and Animation blog posts.